Contents

part III: the person

'This

also shows what the identity of

the same man exists in

namely a participation in the same

continued life

by constantly fleeting particles

of matter

that are successively vitally

united to the same organized body.'

John

Locke (1632-1704) in:

'Essay Concerninbg Human

Understanding

- XVII, identity and diversity 6'

Introduction

Control,

identity en the ideal

In part II

have

we dealt with the principles. With

them we arrived from the art of

analysis at what we call spiritual

association, the spirituality. We

saw how the factor of time played

a part in the relationship between

master and slave: the spirit and

the body. From part I we

already knew that a pure

consciousness is also a matter of

science; a matter of seeing things

as they are, of being free from

illusion. If we nevertheless find

ourselves in a state of illusion

though, if it is so that, even

though we're scientifically in

order and analytically dependable

engaged with the principle, we

turn out not to be unified in the

self of the soul, do we at that

time say that we've fallen down.

Some or another way have we lost

our way in the fallen state and

ran we into bewilderment. We then

have a psychological problem, a

problem of control; in the

illusional state we have a

so-called problem of authority or

we're not pure anymore in the

relation between spirit and body

then, we do not know any longer

who the master and who the slave

would be. With problems of

authority one has illusions of

control: either one is paranoid on

being controlled by others or one

landed in the illusion that the

mission of self-control would

consist of the duty to control

someone else. In the fallen state

does one, departing from an

individual illusion, together with

others slide down in a common

illusion of a 'society' finding

itself in the chaos of the state

of no longer properly cooperating

people.

We

have no clue anymore what we're

up to then, what we're supposed

to do, and who we are. We so

have a problem of identity, a

problem with the servitude and a

problem with the knowledge and

are burdened with the assignment

to solve that problem. Like bees

whose honey was stolen by the

beekeeper, we then get

sugarwater, a surrogate for

temporarily relieving the

greatest hunger until the

integrity is restored with us

having a grip again on our

individual and communal life.

The problem of identity we solve

provisionally with

ego-ambitions: better to keep up

appearances with an I-prophesy

than give it up all together. We

likewise solve the problem of

servitude as well by laboring

for the money, even though we,

with an indefinable and uneasy

feeling of estrangement, have

our heart no longer to it. It's

a big lie that self-interest not

so precise with the rules, but

O.K. And the problem of

knowledge we solve by reading

out aloud sermons with or

without the help of

'thought-protheses' or books.

Also fine, all that pedantry of

'sir minister'. No longer seeing

it as clearly, no longer being

as conversant, one uses

spectacles, one uses 'mentures'

or a 'thought-prothesis', a

book. That

book also is but an artificial,

not really to the here-and-now

adapted, fixation, but just as

with the glasses that have a

fixed lens-focus, is one

satisfied with one's favorite

author or holy scripture for

that matter. Thus received e.g.

the controversial novel Catcher

in the Rye of J.D. Salinger (born

1919) from 1951, a cult-status

for being the support and refuge

for loners and dropouts who lost

it with the lies of bourgeois

materialism. The book shows, in

the struggle for adulthood of

the leading character Holden,

the world of the 'phonies', the

fake-people or the hypocrites,

but of course is the book itself

also but a fake-idea and

factually thus caught in a

projection. With books holier

the advise is then 'judge not'

or is it like Vy‚sa says (in

S.B. 11.28:

1): 'be

free from praise and criticism

with regard to someone else's

actions'. All those before

mentioned cases of temporary

solutions we call the

compensations of a failed

identity, a failed servitude and

a failed integrity of knowing.

If we don't want to get sick of

it, do we, in order to remedy

that, in fact consequently have

to reason back to the point

where it went wrong, were we

came to a fall, but do we

thereupon see our way blocked by

a couple of psychological

mechanisms. One apparently came

to a fall, but one has to keep

one's faith in oneself and so

one made it a life of justifying

the fall-down and is one not

just as easily capable any more

to figure out on one's own

accord what exactly the fall

down or the rising to one's feet

would be. Something has

disappeared into the

'unconscious'. And even

though one so now and then sees

some half of the truth in one's

sleep or in an upsurge of

intelligence, one very quickly,

like being one's own enemy, then

pushes that away again. For it's

not possible to say to yourself

all the time that you're wrong,

or were wrong at all even, and

that you'd be at odds or not

good-willing. Those who do

engage in telling that

themselves without a further

plan, find themselves in the

grip of a so-called depression:

they cannot retrieve their

self-esteem and motivation

anymore for they are overwhelmed

by the contrary of a closet full

of things tucked away that all

at once, in a crisis, fell over

them and crushed their

self-respect. Thus are we in our

normal waking state 'consonant

with ourselves' as the

psychologists call it (viz. the

social psychologist Leon

Festinger

1919-1989), and are we our best

friend as we already saw in the

Small

Philosophy of Association, and

do we rather distrust the other

than ourselves with the notion:

'when I'm not able to get on top

of things, then you for sure

neither - but if you act as if

you would then I for sure are

better off in facing the

problem' - even though I'm just

as well down in the dark then.

Thus there's never an end to the

psychological complexes and

together we so go downhill when

we as 'friends of ourselves' do

not manage to know the

compensations, to cut with them,

as we already saw, and then get

out of it all together with a

better order of time being more

grounded in the discipline. To

keep our health we have to

escape the temporary provision

of compensations, that bad

system that separated time from

place and reduced it all to a

linear rut and thus disturbed

our dynamical feeling of life of

being connected with the planet

and with each other. That

book also is but an artificial,

not really to the here-and-now

adapted, fixation, but just as

with the glasses that have a

fixed lens-focus, is one

satisfied with one's favorite

author or holy scripture for

that matter. Thus received e.g.

the controversial novel Catcher

in the Rye of J.D. Salinger (born

1919) from 1951, a cult-status

for being the support and refuge

for loners and dropouts who lost

it with the lies of bourgeois

materialism. The book shows, in

the struggle for adulthood of

the leading character Holden,

the world of the 'phonies', the

fake-people or the hypocrites,

but of course is the book itself

also but a fake-idea and

factually thus caught in a

projection. With books holier

the advise is then 'judge not'

or is it like Vy‚sa says (in

S.B. 11.28:

1): 'be

free from praise and criticism

with regard to someone else's

actions'. All those before

mentioned cases of temporary

solutions we call the

compensations of a failed

identity, a failed servitude and

a failed integrity of knowing.

If we don't want to get sick of

it, do we, in order to remedy

that, in fact consequently have

to reason back to the point

where it went wrong, were we

came to a fall, but do we

thereupon see our way blocked by

a couple of psychological

mechanisms. One apparently came

to a fall, but one has to keep

one's faith in oneself and so

one made it a life of justifying

the fall-down and is one not

just as easily capable any more

to figure out on one's own

accord what exactly the fall

down or the rising to one's feet

would be. Something has

disappeared into the

'unconscious'. And even

though one so now and then sees

some half of the truth in one's

sleep or in an upsurge of

intelligence, one very quickly,

like being one's own enemy, then

pushes that away again. For it's

not possible to say to yourself

all the time that you're wrong,

or were wrong at all even, and

that you'd be at odds or not

good-willing. Those who do

engage in telling that

themselves without a further

plan, find themselves in the

grip of a so-called depression:

they cannot retrieve their

self-esteem and motivation

anymore for they are overwhelmed

by the contrary of a closet full

of things tucked away that all

at once, in a crisis, fell over

them and crushed their

self-respect. Thus are we in our

normal waking state 'consonant

with ourselves' as the

psychologists call it (viz. the

social psychologist Leon

Festinger

1919-1989), and are we our best

friend as we already saw in the

Small

Philosophy of Association, and

do we rather distrust the other

than ourselves with the notion:

'when I'm not able to get on top

of things, then you for sure

neither - but if you act as if

you would then I for sure are

better off in facing the

problem' - even though I'm just

as well down in the dark then.

Thus there's never an end to the

psychological complexes and

together we so go downhill when

we as 'friends of ourselves' do

not manage to know the

compensations, to cut with them,

as we already saw, and then get

out of it all together with a

better order of time being more

grounded in the discipline. To

keep our health we have to

escape the temporary provision

of compensations, that bad

system that separated time from

place and reduced it all to a

linear rut and thus disturbed

our dynamical feeling of life of

being connected with the planet

and with each other.

With

one's looking for solutions

arriving at the compensations of

the ego, the labor and the

books, we also get into trouble

with the person. The other may

physically not rule us over,

that we have to do ourselves.

That we remembered from our

education: we have to be grown

up and take our responsibility.

Your daddy and mom aren't there

any  longer

and you even rejoice in it. But

by making yourself the authority

will the other not just like

that be appreciative of or

subservient to that ego, for the

other person knows that game of

compensations very well himself.

We do not without a problem

expect the other to be holy in

following the principles and

thus one assumes that everyone

must be compensating, for that's

something normal. The division

stays and despair dominates

one's life-experience, for one

carries water to the sea with

it: nothing is won with a

(notion of a) charade, there's

no real progress then. For the

materially motivated ego of

outer appearances existing there

for it's own sake is not the

solution really. And that's also

true for paid labor and books.

If one does one's job for the

money only, one is not really

dependable and books most of the

time are a lot of grousing with

a glaze of a partly

self-invented world from which

one also has to wake up again to

discover that, even though one

might dream, one in reality is

still implacably the slave of

the circumstances and the senses

thereto, in stead of being the

master of one's fate. And thus

we are what the british

psychiatrist R. D.

Laing

(1927-1989) in the sixties

called the, circumstantially

created, divided self of the man

who outside is a fool victimized

by the compensation culture with

all her fake appearances and

conflicting psychology, but at

the inside is a god full of

ideals and qualities opposed to

that with a certain frustration

over the inability to realize

oneself, to prove oneself. longer

and you even rejoice in it. But

by making yourself the authority

will the other not just like

that be appreciative of or

subservient to that ego, for the

other person knows that game of

compensations very well himself.

We do not without a problem

expect the other to be holy in

following the principles and

thus one assumes that everyone

must be compensating, for that's

something normal. The division

stays and despair dominates

one's life-experience, for one

carries water to the sea with

it: nothing is won with a

(notion of a) charade, there's

no real progress then. For the

materially motivated ego of

outer appearances existing there

for it's own sake is not the

solution really. And that's also

true for paid labor and books.

If one does one's job for the

money only, one is not really

dependable and books most of the

time are a lot of grousing with

a glaze of a partly

self-invented world from which

one also has to wake up again to

discover that, even though one

might dream, one in reality is

still implacably the slave of

the circumstances and the senses

thereto, in stead of being the

master of one's fate. And thus

we are what the british

psychiatrist R. D.

Laing

(1927-1989) in the sixties

called the, circumstantially

created, divided self of the man

who outside is a fool victimized

by the compensation culture with

all her fake appearances and

conflicting psychology, but at

the inside is a god full of

ideals and qualities opposed to

that with a certain frustration

over the inability to realize

oneself, to prove oneself.

This

section deals with the

restoration of that respect for

the person that one in one's

full glory is at the inside,

about the cure, the becoming,

which the psychologist Carl Rogers

(1902-1987) in 1974 called

'becoming a person'. It's about

the emphatically approached

person who consequently is able

to get back on his feet again

with the realization of what

actually the fallen state would

be, what exactly at the moment

would be his flaws of reasoning,

his errors, his confusion on

norms, standards and needs, and

what his foolishness would be.

But it is also about the person

not so much of compensation, the

person who is of God or who is a

god himself and who constitutes

an ideal, is the redeemer, the

great leader, the savior, the

spiritual master, the hero and

the great beacon, the example,

the source of wisdom and the

control over the universe in the

flesh. The latter is inevitable:

desiring respect for the person

one is oneself, will the other

person also have to be

respected, if one wants to put

an end to the discord of the

material ego-interest. The at

first instance, more or less

being infatuated, realizing of

the inequality with a high - or

sometimes too high - opinion of

that other person in the form of

a Great Personality, is there

because of the karmic reaction

of tipping over to the other

extreme of having respect, for

the control of the equilibrium

wasn't there without a problem.

As a

child one realized oneself maybe

one's father, as an adult that

continues with the ideal of a

godhead who also carries the

name of the Father then. And for

not a few consists the problem

of selfrealization of the fact

that indeed Great Personalities

do exist, whether still around

or not anymore, to look up to

and to learn from. To rid

oneself of the inequality is

there, also according the Great

Personalities, the need of a

process of emancipation, a

process of becoming equal, a

process of spiritual growth, a

therapeutic process. Out of fear

for the false ego of the man of

appearances and lies, do we

therewith following speak of the

holiness that's supposed to be

free from it and of which we

hope it is not sanctimonious

like it is with e.g. priests

violating kids, popes who ordain

the death of others, sect

leaders driving for suicide and

spiritual leaders out for their

own material advantage. We so

speak of belief: in the fallen

state it is difficult to believe

and has one a problem of

authority, but back on one's

feet one all of a sudden

recognizes an ally in that

example that offers support and

so is thus finding faith in a

leader, a Lord, a therapist

and/or a guru the way out of the

fallen state. And that's not

only true for the holiness, no,

an artist honestly capable of

grousing at all the

sanctimoniousness is preferred

over the obedient citizen who

wasn't quite as capable of being

artful with that less wanted

presentation of the truth.

Sometimes is the interest of the

ideal overruled by the interest

of it's manifestation. And that

can be a shocking discovery with

the example of therapists ending

in bed with their clients or

gurus who almost

incomprehensibly take over your

sexual karma and the rest of it. As a

child one realized oneself maybe

one's father, as an adult that

continues with the ideal of a

godhead who also carries the

name of the Father then. And for

not a few consists the problem

of selfrealization of the fact

that indeed Great Personalities

do exist, whether still around

or not anymore, to look up to

and to learn from. To rid

oneself of the inequality is

there, also according the Great

Personalities, the need of a

process of emancipation, a

process of becoming equal, a

process of spiritual growth, a

therapeutic process. Out of fear

for the false ego of the man of

appearances and lies, do we

therewith following speak of the

holiness that's supposed to be

free from it and of which we

hope it is not sanctimonious

like it is with e.g. priests

violating kids, popes who ordain

the death of others, sect

leaders driving for suicide and

spiritual leaders out for their

own material advantage. We so

speak of belief: in the fallen

state it is difficult to believe

and has one a problem of

authority, but back on one's

feet one all of a sudden

recognizes an ally in that

example that offers support and

so is thus finding faith in a

leader, a Lord, a therapist

and/or a guru the way out of the

fallen state. And that's not

only true for the holiness, no,

an artist honestly capable of

grousing at all the

sanctimoniousness is preferred

over the obedient citizen who

wasn't quite as capable of being

artful with that less wanted

presentation of the truth.

Sometimes is the interest of the

ideal overruled by the interest

of it's manifestation. And that

can be a shocking discovery with

the example of therapists ending

in bed with their clients or

gurus who almost

incomprehensibly take over your

sexual karma and the rest of it.

With the

negation or recognition of the

other in the struggle for

getting attention for one's own

person is it as with the

legendary Baron

Munchausen who

pulled himself by his own hairs

out of the swamp:  once

one in faith has been converted

to the positive confession, has

one to realize a position of

being liberated, viz to serve

the cause, if one wants to

escape one's swamp. That other

person one eventually is oneself

and who does manage to keep to

the soul, serve the cause and

know his trade, must be clear in

the eye of one's mind. The dutch

psychologist J. J. van der Werff

spoke in 1965 of self-image and

self-ideal in his book with the

same name: it concerns a

division without which a human

being paradoxically can't be

happy or even be healthy and

sane. One is necessarily divided

being honest about the fact that

one inescapably as a person is

of limitations, faults, errors,

misperceptions, and miseries in

one's material life at the one

hand, while at the other one has

to counterbalance with a self

more durably happy, more capable

and of less faults and errors.

The way we from part one to part

two arrived from a person free

from illusion that is one with

the universe at a person

identified with the matter of

not being so sure anymore of the

oneness with the realization of

the good and bad of having

principles, do we from that

innerly divided, analytically

and spiritually seeking man

arrive at the ideal man we must

manage to realize, we must put

faith in as an ever on our

approach receding horizon of

qualities and integrity who we

within ourselves have to realize

as someone knowing his trade

(vedically: is the caittya-guru).

And thus do we, from the

personal realization of our

inability, arrive at the

problems of religion and

politics. once

one in faith has been converted

to the positive confession, has

one to realize a position of

being liberated, viz to serve

the cause, if one wants to

escape one's swamp. That other

person one eventually is oneself

and who does manage to keep to

the soul, serve the cause and

know his trade, must be clear in

the eye of one's mind. The dutch

psychologist J. J. van der Werff

spoke in 1965 of self-image and

self-ideal in his book with the

same name: it concerns a

division without which a human

being paradoxically can't be

happy or even be healthy and

sane. One is necessarily divided

being honest about the fact that

one inescapably as a person is

of limitations, faults, errors,

misperceptions, and miseries in

one's material life at the one

hand, while at the other one has

to counterbalance with a self

more durably happy, more capable

and of less faults and errors.

The way we from part one to part

two arrived from a person free

from illusion that is one with

the universe at a person

identified with the matter of

not being so sure anymore of the

oneness with the realization of

the good and bad of having

principles, do we from that

innerly divided, analytically

and spiritually seeking man

arrive at the ideal man we must

manage to realize, we must put

faith in as an ever on our

approach receding horizon of

qualities and integrity who we

within ourselves have to realize

as someone knowing his trade

(vedically: is the caittya-guru).

And thus do we, from the

personal realization of our

inability, arrive at the

problems of religion and

politics.  The

religion is the social

organization of the respect for

the ideal person in the context

of a certain order of time, and

the political constitutes the

actuality of the problematic,

but necessary respect for also

the maybe not always as holy

person, in which one is engaged

in telling each other what

actually should be the order of

time in 'reality', how late it

'really' is and how the book of

law 'actually' should look like.

What would now be the priority

of the needs of the necessary

succession of deeds - like the

humanist and psychologist A. Maslow (1908-1970)

put it - once we at the one hand

religiously know of the Original

Person while we in terms of

behavioral science at the other

hand have accepted as being

inevitable - with or without a

so-called peak-experience of

being on our way - what the

ideal is of that person who in

India is called the purusha?

How to tell each other how late

it is, or what we're up to, with

the religion and with the

politics? Or .... was it, as we

already saw in part I and II,

more a matter of self-control

and sense of reality, that

identifying ourselves with the

great example of self-control of

the Controller of Yoga, who in

case of proven wisdom and

recognizable incarnation

vedically also is given the

honorary title of yogis'vara? The

religion is the social

organization of the respect for

the ideal person in the context

of a certain order of time, and

the political constitutes the

actuality of the problematic,

but necessary respect for also

the maybe not always as holy

person, in which one is engaged

in telling each other what

actually should be the order of

time in 'reality', how late it

'really' is and how the book of

law 'actually' should look like.

What would now be the priority

of the needs of the necessary

succession of deeds - like the

humanist and psychologist A. Maslow (1908-1970)

put it - once we at the one hand

religiously know of the Original

Person while we in terms of

behavioral science at the other

hand have accepted as being

inevitable - with or without a

so-called peak-experience of

being on our way - what the

ideal is of that person who in

India is called the purusha?

How to tell each other how late

it is, or what we're up to, with

the religion and with the

politics? Or .... was it, as we

already saw in part I and II,

more a matter of self-control

and sense of reality, that

identifying ourselves with the

great example of self-control of

the Controller of Yoga, who in

case of proven wisdom and

recognizable incarnation

vedically also is given the

honorary title of yogis'vara?

Contents

section IIIa: the personal

Self-knowledge,

reformation and identity

'God, like the tradition

tells us,

has in His grip the beginning, the

middle and the end of all things

and in His fixed course, according

nature,

takes He everything to it's

destination.

Him always accompanies DikŤ2, of

retribution

to all who do not fulfill the

divine law.

Who wants to be happy and

felicitous,

better respects her from the

beginning.'

Plato quoted by Aristotle

in: About the Cosmos

In the

search for the self of durable

happiness and knowledge we so

cannot escape the person, nor the

necessity to respect that person,

that one is oneself as well, also

in a material sense. Therefore

splits, filognostically, the

respect for the person itself up

in a personal/religious and a

political/futurological section.

With the personal do we in our

scientifically founded, methodical

selfrealization wrestle with the

holiness and the authentic

experience of the 'Absolute

Truth', and concerned with the

material interest do we wrestle

with the politics of time-systems,

identities, commentaries, the

authority, the last word, the

advantage of doubt, the law, the

economy, the responsibility and

the future, that we as adults to

it, as we just saw, with the

necessity of a certain self-ideal,

also need.

From

part one we already knew to make

for a good division in accord

with the order of nature, an

order which, lawful as it is,

provides certainty, offers the

certain knowledge that cannot be

doubted by anyone. On the basis

of this certainty we in part two

arrived at the bold venture of

learning the art to live with

the duality inherent to the

analytical and with the

qualities inherent to the

spiritual self we cannot live

without either with the

philosophy of liberation. Now,

having arrived at the interest

of the person, are we faced with

the question that is classical:

'who am I?'. Vedically the

answer is simply 'soham'

which literally means 'I

myself'. One also says 'tat

tvam asi' or 'that thou

art' to indicate that the

reality of the I contains a

relation with the reality and

the principle (tat) of

the universe comprising the

other. Without that relation

carries the I-awareness with God

no reality. The I without the

other is, considering the

inevitability of the duality, an

illusion of separateness that

must be overcome with what

vedically is called karuna,

day‚, bh‚va or prema:

kindness, compassion, affection

and love. From Plato we in the

West learned also that God, or

better stated the way to God,

must be considered the good

which with Vy‚sa is called

sattva or the mode (guna)

of goodness (S.B.

7.15: 25).

Sinful acting is thus seen

nothing but the acting which,

causing sorrow and grief, goes

against the goodness, and

serving God is the consequence

of devoting oneself to this

realization of the I that then

no longer is called false but is

called a soul, a conscientious

self of principles, of norms and

standards. As for the concept of

God says Aristotle in About

the Cosmos: 'God is one,

but with many names, derived

from all phenomena he time and

again brings about, he is

addressed ' .... he is called

the son of kronos and the Time

(Chronos), because his existence

continues from the one endless

eon on earth to the other; ...I

also dare say that 'Necessity'

is but another name for him,

since he is the invincible cause.'

The discovery of this True Self

of the soul of this Original

Person, who thus according the

greek root of philosophy is also

identified with the concept of

time and necessity, can, via the

mode of goodness not take place

but along the ways of having

respect for the other who we,

with ourselves included, may not

cause any grief. The ego in his

falsehood poises itself against

the negativity about all the

rest that needs to be excluded

for the sake of material action,

we saw in the

NOT-paradigm of part I. That

negation, that denial of saying

no, is essential for one's

material action. It can't be

otherwise. For the practice of

Christianity we in Europe thus

at the end of the Middle Ages

knew, with this saying in mind,

Martin

Luther

(1483-1546) who

exposed the fallen state of the

fundamentalistic-dictatorial

influence of the Catholic

Church. Result of his heroism

was that the church after due

centuries of struggling on was

dethroned from that position of

absolute power and had to learn,

just like any other possible

form of class-corruption, neatly

and modestly to settle for a

normal position in the

fields of action of the

individual citizen as discussed

in part I. Christianity was at

the end of the Middle Ages no

longer the same Christianity,

but had collapsed into a

theology divided in itself, a

factually fallen culture that

later on difficulty facing the

lesson of the philosophy of

Enlightenment as a lecture in

adulthood and (also religious)

self-responsibility. Pope

Gregory's calendar-reform

shortly after the Middle Ages

1582 wouldn't be of much avail

against that confusion. There

was more at stake than the

matter of the order of time. The

system in it's entirety didn't

accord any longer with nature,

but the

reformist/contra-reformist

restoring with a rule of time

that respect for the reality of

God's creation couldn't revoke

the dividedness that had risen,

despite of all the burning of

heretics and breaking of idols.

Like Thomas

Kuhn (1922

- 1996) pointed it indirectly

out in 1962 with his study about

the nature of the revolutions of

scientific paradigms, followed

in the year zero the thought

model of Christianity a

revolutionary way that model of

Judaism and followed Islam seven

centuries later historically

with the same heroism the

Christian vision, whereupon next

after the revival of the

greco-roman culture in the

Renaissance around 1650 followed

the culture of Enlightenment with

at least as much rebel valor.

Enlightenment thrived on the

eroded religious authority which

in fact already since the rise

of Islam with the repression of

their argument of time had to

face it's decay. Islam had

developed the praying to the

position of the sun with the

discovery by Mohammed

(571-632) in the seventh century

after Christ of that

'opportunity in de religious

market' and had thus risen to

success over the Christians who

outside the monasteries weren't

that conscientious with the

order of the times of prayer.

For during the Middle Ages was

the julian calendar with it's

kalends and ides-days there only

for the monastics, for the

citizens it had been abolished

as early as with the roman

emperor Constantine

the Great

(272-337). who

exposed the fallen state of the

fundamentalistic-dictatorial

influence of the Catholic

Church. Result of his heroism

was that the church after due

centuries of struggling on was

dethroned from that position of

absolute power and had to learn,

just like any other possible

form of class-corruption, neatly

and modestly to settle for a

normal position in the

fields of action of the

individual citizen as discussed

in part I. Christianity was at

the end of the Middle Ages no

longer the same Christianity,

but had collapsed into a

theology divided in itself, a

factually fallen culture that

later on difficulty facing the

lesson of the philosophy of

Enlightenment as a lecture in

adulthood and (also religious)

self-responsibility. Pope

Gregory's calendar-reform

shortly after the Middle Ages

1582 wouldn't be of much avail

against that confusion. There

was more at stake than the

matter of the order of time. The

system in it's entirety didn't

accord any longer with nature,

but the

reformist/contra-reformist

restoring with a rule of time

that respect for the reality of

God's creation couldn't revoke

the dividedness that had risen,

despite of all the burning of

heretics and breaking of idols.

Like Thomas

Kuhn (1922

- 1996) pointed it indirectly

out in 1962 with his study about

the nature of the revolutions of

scientific paradigms, followed

in the year zero the thought

model of Christianity a

revolutionary way that model of

Judaism and followed Islam seven

centuries later historically

with the same heroism the

Christian vision, whereupon next

after the revival of the

greco-roman culture in the

Renaissance around 1650 followed

the culture of Enlightenment with

at least as much rebel valor.

Enlightenment thrived on the

eroded religious authority which

in fact already since the rise

of Islam with the repression of

their argument of time had to

face it's decay. Islam had

developed the praying to the

position of the sun with the

discovery by Mohammed

(571-632) in the seventh century

after Christ of that

'opportunity in de religious

market' and had thus risen to

success over the Christians who

outside the monasteries weren't

that conscientious with the

order of the times of prayer.

For during the Middle Ages was

the julian calendar with it's

kalends and ides-days there only

for the monastics, for the

citizens it had been abolished

as early as with the roman

emperor Constantine

the Great

(272-337).

But the islamic

uniformity and one-sidedness of

that option was thus to the logic

of the fields of human action also

doomed to perish

(fundamentalistically). With the

philosophy of Enlightenment came not

just the Church to a fall but also

Islam and was she, since the

historical turning-point of the

siege of Vienna in 1683 where the

Ottoman rule of Islam was defeated

by the polish king Jan III

Sobiesky

(1629-1696), assigned her further

as historical to be denoted use

and position. The idea of

enlightenment which, in a violent

manner facing itself politically,

in the enlightened democracy of

today still finds it's expression

in the motto of the European Union

of 'oneness in diversity', was not

an original idea of Martin Luther

though, who only from a sober and

self-responsible properly being

versed in the scripture in a

reformatory way had preached

against the indulgences, and not

so much had aimed at a diversity

of religious and scientific

practices. Also for him there was

but one Lord. The notion of

oneness in diversity in the

enlightened multicultural sense we

find back, these days politically

with the modern rise of the spirit

of democracy, with another

religious reformer of the period:

the vaishnava saint and avat‚ra

S'rÓ

Caitanya Mah‚prabhu

(1486-1543), who with that motto

in India had attacked the false

authority of as well the also

there dominating rule of Islam,

the dry theology of books and the

caste-system. He was the factual

Lord of that notion of

enlightenment and it was He who

put forward as being the most

important Bible in that theology

the S'rÓmad

Bh‚gavatam or the Bh‚gavata

Pur‚na as being

the one essential story of the

person of God as being the

Fortunate One, which had flowed

from the hand of our filognostic

philosopher of duty Vy‚sa.  Even

though Luther defended a principle

of religious purification, still

was his ego-motivated effort for a

Bible readable to each, the not

cherishing of any celibate

preference and not selling of

indulgences any longer, a material

effort. The principle of the

spiritual union of the church

founded on the, in fact gnostic,

sanctity and sainthood, which one

indeed rarely finds with normal

and also clerical mortals, was

dropped by him as being impure.

And that made his action material.

He was of no mercy with the

material digression of the unholy

fathers of the church, but was

with the neglect of the sanctity

of the spiritual union himself a

materialist also; or, as the guru

Osho it in so many words explained

to his 'new men': 'the one saying

no is not free from it yet'. With

Luther we can observe how

fundamentalism - see also the

page about the fields with part

one - itself

is also a form of materialism: in

pushing itself off against the

more moderate, political

'materialistic' people of

compromise and with the exclusion

and even killing of alleged

sinners do they, just as catholic

contrareform itself also again

did, make for a false ego not

really willing to be of sacrifice

for the needed reconciliation.

Religious fanaticism is there of a

lack of philosophy so explained

one day Swami

A.C. Bhaktivedanta Prabhup‚da

(1896-1977), the

leader of the Hare

Krishna's to them,

one day sighing about the reprove

at their address of being

sectarian. And too much of

philosophy gives one the dry,

loveless books-estrangement of the

scientists, he added thereto.

Therewith seemed also of the

sanctity the austerity in

celibacy, that is not just

respected by the catholic orders,

but also, together with the

analysis, the penance and the yoga

is respected in India as a holy

principle of spiritual knowledge,

altogether false with the fall of

catholic Rome. Martin Luther

though being a hero, was not a

saint in this sense. He had, be it

with some difficulty and noble

protection, like a Jesus not to

carry the cross of violence of the

Reformation which indeed had to be

carried by the monasterial

celibates who were persecuted here

and there, whether they were

corrupt or not. In fact was that

cross in that period of spiritual

confusion about the norms and

standards on the shoulders of Lord

Caitanya, who with his grace for

the karma of philosophical

scholarship and religious

sanctimoniousness also for real

sacrificed his sane mind (and

before that his marriage) and thus

for that matter may be considered

the Christ of it. Luther married,

not sacrificing his sane mind for

the sake of his devotion to God,

simply modestly and in solidarity

with the common man, with a by the

populace from her convent banished

nun. With him, and the rest of the

thus reacting Christians - as for

the mob follows the leader -

flared up in that thus found

material self-interest of a

simple, but sacramentally also

commendable and not unholy, Even

though Luther defended a principle

of religious purification, still

was his ego-motivated effort for a

Bible readable to each, the not

cherishing of any celibate

preference and not selling of

indulgences any longer, a material

effort. The principle of the

spiritual union of the church

founded on the, in fact gnostic,

sanctity and sainthood, which one

indeed rarely finds with normal

and also clerical mortals, was

dropped by him as being impure.

And that made his action material.

He was of no mercy with the

material digression of the unholy

fathers of the church, but was

with the neglect of the sanctity

of the spiritual union himself a

materialist also; or, as the guru

Osho it in so many words explained

to his 'new men': 'the one saying

no is not free from it yet'. With

Luther we can observe how

fundamentalism - see also the

page about the fields with part

one - itself

is also a form of materialism: in

pushing itself off against the

more moderate, political

'materialistic' people of

compromise and with the exclusion

and even killing of alleged

sinners do they, just as catholic

contrareform itself also again

did, make for a false ego not

really willing to be of sacrifice

for the needed reconciliation.

Religious fanaticism is there of a

lack of philosophy so explained

one day Swami

A.C. Bhaktivedanta Prabhup‚da

(1896-1977), the

leader of the Hare

Krishna's to them,

one day sighing about the reprove

at their address of being

sectarian. And too much of

philosophy gives one the dry,

loveless books-estrangement of the

scientists, he added thereto.

Therewith seemed also of the

sanctity the austerity in

celibacy, that is not just

respected by the catholic orders,

but also, together with the

analysis, the penance and the yoga

is respected in India as a holy

principle of spiritual knowledge,

altogether false with the fall of

catholic Rome. Martin Luther

though being a hero, was not a

saint in this sense. He had, be it

with some difficulty and noble

protection, like a Jesus not to

carry the cross of violence of the

Reformation which indeed had to be

carried by the monasterial

celibates who were persecuted here

and there, whether they were

corrupt or not. In fact was that

cross in that period of spiritual

confusion about the norms and

standards on the shoulders of Lord

Caitanya, who with his grace for

the karma of philosophical

scholarship and religious

sanctimoniousness also for real

sacrificed his sane mind (and

before that his marriage) and thus

for that matter may be considered

the Christ of it. Luther married,

not sacrificing his sane mind for

the sake of his devotion to God,

simply modestly and in solidarity

with the common man, with a by the

populace from her convent banished

nun. With him, and the rest of the

thus reacting Christians - as for

the mob follows the leader -

flared up in that thus found

material self-interest of a

simple, but sacramentally also

commendable and not unholy, desire

for offspring, a political

struggle in the period that would

fuel many wars more on the way to

what we now, in search for the

factual authority of reform and

the notion of enlightenment, call

the ideal of democracy. Fine, so

be it, Luther we thus mustn't hold

responsible for the dissension of

the Reformation opposing the

Contrareformation, and so he

didn't think of it himself either.

Of course may only the Lord

himself reform His own religion

and not just a human being with

material needs like Luther who was

but the immediate cause. From

Luther we may learn that normal

karmic persons cannot exist in the

spirit only, but also have to

carry a material burden with the

democratic notion of the equality

of being one in diversity; a

notion which thus with Vy‚sa in

the Bhagavad

GÓt‚ already

thousands of years before was

called ekatvena prithaktvena

bahuda and with Caitanya

anew was preached as the end

conclusion that says acintya

bhed‚bheda tattva: an

inscrutable reality of oneness in

diversity. desire

for offspring, a political

struggle in the period that would

fuel many wars more on the way to

what we now, in search for the

factual authority of reform and

the notion of enlightenment, call

the ideal of democracy. Fine, so

be it, Luther we thus mustn't hold

responsible for the dissension of

the Reformation opposing the

Contrareformation, and so he

didn't think of it himself either.

Of course may only the Lord

himself reform His own religion

and not just a human being with

material needs like Luther who was

but the immediate cause. From

Luther we may learn that normal

karmic persons cannot exist in the

spirit only, but also have to

carry a material burden with the

democratic notion of the equality

of being one in diversity; a

notion which thus with Vy‚sa in

the Bhagavad

GÓt‚ already

thousands of years before was

called ekatvena prithaktvena

bahuda and with Caitanya

anew was preached as the end

conclusion that says acintya

bhed‚bheda tattva: an

inscrutable reality of oneness in

diversity.

A computer

is nothing w ithout an operating

system and a therein operating

program, and so it is also the

other way around. So also is man

not really man without a mutually

agreed upon peace-loving societal

order and a personal conviction or

spirit evolved therein, making for

the integrity and the functioning

of the person in that system. And

thus is there also with the

necessary negation of the

inescapable ego with it something

like the being attached to the

goodness of the platonic God with

which we cannot as easily abandon

the selfhood that manifests itself

time and again with the normal

mortal that is karmically

connected to mother earth, so that

more values are needed than just

the one of goodness to do justice

to God in terms of eternal values.

With Lord Caitanya as the actual

Lordship of Reform and defender of

the philosophy of Vy‚sadeva, we so

find therefore, next to his very

emotional relations or mellows (rasas)

with the holy name that in ecstasy

was sung by him, the s'uddha

sattva values of the s'auca,

tapas, sathya and d‚ya

as explained by Vy‚sa (in S.B.

1.17: 24), or the

need of the respectively with the

to the values with the good of God

finding of the purity of body and

mind, penance, truthfulness and a

nature-loving compassion. For the

goodness with oneself without

compassion might imply violence

against others (including plant

and animal); might imply a lack of

penance in not sharing with

'lesser ones'; might imply a lie

in the description of reality

because of which the goodness in

fact turns out to be an illusion;

and, with a lusty type of goodness

being estranged and lonesome,

imply the faithlessnesss of the

inability to live the

connectedness; or as Vy‚sa puts

it: (S.B.

11.25: 35) 'Being

connected should he also, free

from depending on it, conquer the

goodness so that he, with his

intelligence pacified in being

liberated from the gunas, as an

individual soul giving up on the

cause of his being conditioned,

achieves Me.' of the

inescapable ego with it something

like the being attached to the

goodness of the platonic God with

which we cannot as easily abandon

the selfhood that manifests itself

time and again with the normal

mortal that is karmically

connected to mother earth, so that

more values are needed than just

the one of goodness to do justice

to God in terms of eternal values.

With Lord Caitanya as the actual

Lordship of Reform and defender of

the philosophy of Vy‚sadeva, we so

find therefore, next to his very

emotional relations or mellows (rasas)

with the holy name that in ecstasy

was sung by him, the s'uddha

sattva values of the s'auca,

tapas, sathya and d‚ya

as explained by Vy‚sa (in S.B.

1.17: 24), or the

need of the respectively with the

to the values with the good of God

finding of the purity of body and

mind, penance, truthfulness and a

nature-loving compassion. For the

goodness with oneself without

compassion might imply violence

against others (including plant

and animal); might imply a lack of

penance in not sharing with

'lesser ones'; might imply a lie

in the description of reality

because of which the goodness in

fact turns out to be an illusion;

and, with a lusty type of goodness

being estranged and lonesome,

imply the faithlessnesss of the

inability to live the

connectedness; or as Vy‚sa puts

it: (S.B.

11.25: 35) 'Being

connected should he also, free

from depending on it, conquer the

goodness so that he, with his

intelligence pacified in being

liberated from the gunas, as an

individual soul giving up on the

cause of his being conditioned,

achieves Me.'

The

personal part of our filognosy

thus commences with the individual

story of this writer. Not that my

small I-ness would be that

important, but because my person

knows the history which

illustrates this development of

being attached to the good,  towards

the being detached in the goodness

which is so essential to the

progress of escaping from the

prison and the hopeless stupidity

of civil attachments. For the

question at hand is here: how in

God's name does one get as far as,

e.g., a Christian to occupy

oneself with Hinduism, the

inevitable cultural consequence of

respecting Vy‚sa? What exactly was

the need thereof, how does such a

life-experience build up? Of

course am I personally but one of

the many examples of people who,

lost in modern time, had to

reconsider things for themselves

with the notion that the classical

order of christian society is not

quite fully of understanding and

prepared to welcome someone with

all the twists of our modern fate.

The order of the world is the

order of the world and

Christianity, like Judaism and

Islam is but a historical part of

it, however indispensable they on

themselves are for so many. And so

met the writer of this in his

life, departing from the christian

cross, with other cultures of the

sun, moon, order and gnosis, who

contributed in the love for the

knowledge which in the end

amounted to the filognosy of this

site. The ongoing realization with

this was that repressive progress,

the evolution at the cost of

previous developments, constitutes

no real progress. A tree is

healthy together with its roots

and so is our political,

democratic and postmodern,

enlightenment healthy with the

vedic root, even though it is,

like the GÓt‚ (15: 1-4) puts

it, a tree up side down that with

it's roots touches the sky, and

with which one has to break in the

end when the jog is done and the

tools may be cleared away. One

gains experience all together and

everything else that is found with

it simply complicates the matter.

The fact that there are material

improvements taking place as e.g.

the tape-recorder finding digital

recording technologies or of the

phone evolving into the

communication over the internet,

doesn't mean that that culture or

school of learning of the medium

that historically preceded another

institute of civilization wouldn't

be of any use anymore or wouldn't

have a right to exist any longer.

The vinyl-record is still around,

despite of CD's and also is the

radio still there despite of the

t.v. Despite of the internet are

there still books and despite of

Christianity is there still

Judaism too, just like the culture

is still around of the 'sons of

God' towards

the being detached in the goodness

which is so essential to the

progress of escaping from the

prison and the hopeless stupidity

of civil attachments. For the

question at hand is here: how in

God's name does one get as far as,

e.g., a Christian to occupy

oneself with Hinduism, the

inevitable cultural consequence of

respecting Vy‚sa? What exactly was

the need thereof, how does such a

life-experience build up? Of

course am I personally but one of

the many examples of people who,

lost in modern time, had to

reconsider things for themselves

with the notion that the classical

order of christian society is not

quite fully of understanding and

prepared to welcome someone with

all the twists of our modern fate.

The order of the world is the

order of the world and

Christianity, like Judaism and

Islam is but a historical part of

it, however indispensable they on

themselves are for so many. And so

met the writer of this in his

life, departing from the christian

cross, with other cultures of the

sun, moon, order and gnosis, who

contributed in the love for the

knowledge which in the end

amounted to the filognosy of this

site. The ongoing realization with

this was that repressive progress,

the evolution at the cost of

previous developments, constitutes

no real progress. A tree is

healthy together with its roots

and so is our political,

democratic and postmodern,

enlightenment healthy with the

vedic root, even though it is,

like the GÓt‚ (15: 1-4) puts

it, a tree up side down that with

it's roots touches the sky, and

with which one has to break in the

end when the jog is done and the

tools may be cleared away. One

gains experience all together and

everything else that is found with

it simply complicates the matter.

The fact that there are material

improvements taking place as e.g.

the tape-recorder finding digital

recording technologies or of the

phone evolving into the

communication over the internet,

doesn't mean that that culture or

school of learning of the medium

that historically preceded another

institute of civilization wouldn't

be of any use anymore or wouldn't

have a right to exist any longer.

The vinyl-record is still around,

despite of CD's and also is the

radio still there despite of the

t.v. Despite of the internet are

there still books and despite of

Christianity is there still

Judaism too, just like the culture

is still around of the 'sons of

God'  who

arriving from beyond the mountains

- possibly the far east thus -

exerted their influence upon the

Jews, like the Bible-book Genesis

describes it in the chapter on the

Ancient Times. So too do we later

on in the political section arrive

at the conclusion that with

respect for a certain history of

the norms and standards we simply

have to count with the different

views there are in the world and

that we so also have to count with

the different personalities,

divine or not, like they are taken

together filognostically at this

site (and in the

book thereof) with

the different sections mentioning

them. In fact is only

non-repressively operating the

respect found for the human rights

and a proper idea of emancipation

in de direction of the beatitude,

and so is it safe to say that only

with a syncretic approach, a kind

of filognosy as expounded here, a

realistic respect for the person

and his association and a politics

of mutual commenting is possible

that offers a future to all. The

repression that was born from a

lack of talent leads corrupting to

dictatorship, but the filognosy

that leads to respect for all the

different views leads, as was

described already in the Small

Philosophy of Association, to the

balance of a true democracy, to a

more at the human identity of the

soul directed representative

democracy which no longer defeats

itself, just like a couple of

football-teams all the time do,

with a new option of sovereignty

with every election. who

arriving from beyond the mountains

- possibly the far east thus -

exerted their influence upon the

Jews, like the Bible-book Genesis

describes it in the chapter on the

Ancient Times. So too do we later

on in the political section arrive

at the conclusion that with

respect for a certain history of

the norms and standards we simply

have to count with the different

views there are in the world and

that we so also have to count with

the different personalities,

divine or not, like they are taken

together filognostically at this

site (and in the

book thereof) with

the different sections mentioning

them. In fact is only

non-repressively operating the

respect found for the human rights

and a proper idea of emancipation

in de direction of the beatitude,

and so is it safe to say that only

with a syncretic approach, a kind

of filognosy as expounded here, a

realistic respect for the person

and his association and a politics

of mutual commenting is possible

that offers a future to all. The

repression that was born from a

lack of talent leads corrupting to

dictatorship, but the filognosy

that leads to respect for all the

different views leads, as was

described already in the Small

Philosophy of Association, to the

balance of a true democracy, to a

more at the human identity of the

soul directed representative

democracy which no longer defeats

itself, just like a couple of

football-teams all the time do,

with a new option of sovereignty

with every election.

First of

all is it with this outlook thus

of importance to offer my own

story as an example and as a

proof of the viability and

necessity of the filognosy for

each. Even though not everyone

shares the same - and thus

better to recognize - experience

or evolution in life, even

though there are many roads that

lead to the same political Rome

of the actual respect for the

person,  still

is every path traveled a gate to

the future to the disposition of

each. That is the proven use of

a self-description one just as

well may consider a failure of

the dominance of the false ego

as a success in selfrealization

in the interest of the greater

soul of the world population in

it's entirety and God with all

living creatures and universes

to it in particular. To begin

with myself are there two pages

with sayings. First a page with

quotes of

people other than me, the way I

happened to find them left and

right about in particular the

subject of time and the order of

wisdom. Like the aphorisms on the

next page that came to me as

separate ideas, must they, not

always wise or even hilarious as

they are at times, not all be

taken as serious. The page with

my own sayings is called the Gray

Page for

that reason. They are partly

absurd thoughts, impulses or

emotional expressions sometimes

just meant for fun or to serve

another emotional reason. After

having presented myself on a

next page in the section called

The

Mirror of Tim' where

I tell the story of how I

arrived at my filognostical

sense of order, is there room

for a page on which I further

deliberate on gurus

and therapists and

focus on the special

incarnations of God in the

present age. Next follows a page

about the idea of time

realized religiously, the

way one sees it with the

different world religions, and

is there as an introduction to next

section a page

about my

personal struggle with the

times of the modern political

quarrel. What

follows next is a page

specifically about the Game

of Order, a

complete site in itself, that

everybody has to learn to play

if he wants to consider himself

a winner and an committed person

- as far as I am concerned a

filognostic. At last is there a

page about the

basis of vedic knowledge on

which this entire site actually

was built. It's beyond the scope

of this site to deal extensively

with the complete of the

vedantic commentary written by

Vy‚sa, but with a general

introduction to that flute in

the hands of Krishna, his hero

and Lordship, and the discussion

of a couple of elementary

chapters and nuclear verses

which especially emphasize the

connection between the order of

time and the person of God, will

religiously committed this

section be completed. still

is every path traveled a gate to

the future to the disposition of

each. That is the proven use of

a self-description one just as

well may consider a failure of

the dominance of the false ego

as a success in selfrealization

in the interest of the greater

soul of the world population in

it's entirety and God with all

living creatures and universes

to it in particular. To begin

with myself are there two pages

with sayings. First a page with

quotes of

people other than me, the way I

happened to find them left and

right about in particular the

subject of time and the order of

wisdom. Like the aphorisms on the

next page that came to me as

separate ideas, must they, not

always wise or even hilarious as

they are at times, not all be

taken as serious. The page with

my own sayings is called the Gray

Page for

that reason. They are partly

absurd thoughts, impulses or

emotional expressions sometimes

just meant for fun or to serve

another emotional reason. After

having presented myself on a

next page in the section called

The

Mirror of Tim' where

I tell the story of how I

arrived at my filognostical

sense of order, is there room

for a page on which I further

deliberate on gurus

and therapists and

focus on the special

incarnations of God in the

present age. Next follows a page

about the idea of time

realized religiously, the

way one sees it with the

different world religions, and

is there as an introduction to next

section a page

about my

personal struggle with the

times of the modern political

quarrel. What

follows next is a page

specifically about the Game

of Order, a

complete site in itself, that

everybody has to learn to play

if he wants to consider himself

a winner and an committed person

- as far as I am concerned a

filognostic. At last is there a

page about the

basis of vedic knowledge on

which this entire site actually

was built. It's beyond the scope

of this site to deal extensively

with the complete of the

vedantic commentary written by

Vy‚sa, but with a general

introduction to that flute in

the hands of Krishna, his hero

and Lordship, and the discussion

of a couple of elementary

chapters and nuclear verses

which especially emphasize the

connection between the order of

time and the person of God, will

religiously committed this

section be completed.

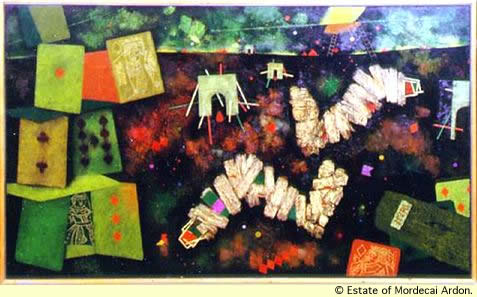

The

pictures:

- The

modern painting is of Mordecai Ardon and is called 'For

the fallen souls'; it is the

center piece called the 'Card

house' from a triptych of 1955 - '56. It is

painted in oil on canvas and is

part of the collection of the

Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam.

- The picture

with the glasses and the book

indicates to what extend a book

equals a pair of glasses, works

like spectacles.

- The man

underneath is the

anti-psychiatrist R. D. Laing, from the sixties who

emphasized the environmental

factors of the societal system as

possible maddeners.

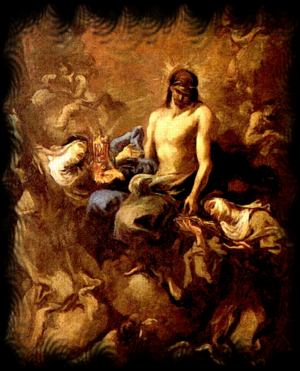

- The

picture of Christ is a painting of

Antonio da Correggio (1489 - 1534)

titled 'Christ presented to the

people' (Ecce Homo); it is

from 1525-30 and consists of oil

on a panel measuring 99.7 x 80 cm,

and is situated in the National

Gallery of London.

- The picture of

the bust is an etching of Gustave

Dorť (1832 - 1883) and shows

Baron von MŁnchhausen. A literary character known for his

grandiose adventures. His story

was also filmed by Jerry

Gilliam.

- The Buddha

is a picture of Maha-Asta

Caitya, the great teacher of

inner renouncement, it is from

Khara Khoto, Central Asia. It is

from before 1227 from the Tangut

Dynasty and can be found in the

Hermitage Museum.

- The nun

with the poor child is Mother

Theresa (1910 - 1997), the holy

Sister of Compassion doing her

charitable work in India.

- Underneath a

portrait of Martin Luther (1483 -

1546), painted by Lucas Cranach

der ńltere in 1529. Luther was the

theologian overturned the catholic

order with his struggle against

the corruption of the church with

her indulgences. He translated the

english text from the Bible in

German and thus popularized the

text. He is considered the leader

of the Christian Reformation.

- The painting

with the monk shows Luther during

the defense of his theses in the reichstag

in april 1521 in Worms in the

presence of emperor Karel V.

Luther refused to revoke anything

of what he had written.

- The

painter with the dancer shows Lord

Krishna Caitanya

Mah‚prabhu (1486-1543) who brought the reform

of vaishnavism which contested the

rule of Islam in India, the

caste-system and the dry

book-knowledge. His message was

'chant the names and spread the

message of the Bh‚gavatam'. In the West he is

known as the Lord of the Hare

Krishna's.

- The painting

of Christ with the nuns is of

Alessandro Magnasco (1667-1749),

and is called 'Christ Adored by

Two Nuns' and is from 1715,

oil on canvas, 58 x 43 cm, at home

in the Galleria dell'Accademia in

Venice.

- The

green painting of mother earth

with her grip on the person is of

Frida Kahlo and named 'The Love

Embrace of the Universe, the

Earth (Mexico), Me, and Senor

Xolotl', and is of 1949, oil

on canvas, 27 1/2 x 23 7/8 and can

be found in the Collection of

Jorge Contreras Chacel in Mexico

City.

- The

picture below represents the

filognostic cross in which the pranava

as the form and yoga-mantra of

God, the sun, the moon and the

celestial sky is respected on the

basis of the gnosis that mediates

in the relation between science

and religion.

- The tree

upside down is a banyan

representing the knowledge of the

world which roots in the heaven of

transcendence.

- The gate

with the light opens one's eye for

the still unknown but brilliant

future reserved for the person of

good will in the filognosy.

- The hands

with the flute represent the hands

of Lord Krishna who bedazzles us

with His love for the harmony of

nature.

Footnote:

2: DikŤ: personification

of justice considered the daughter

of Zeus and Themis.

De

site lineair als een perfectie

van de causale illusie:

|